Removing people with learning disabilities and/or autism from mental health legislation has been a policy goal for organisations campaigning with and for these groups since at least the mid 20th century. This is now being proposed in a government white paper, Reforming the Mental Health Act 1983. There are, broadly speaking, two main reasons for campaign bodies to support the move.

First is a sense that, properly speaking, mental health legislation is not about this population; the “mental disorder” defined in section 1 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) refers to people with “mental illnesses” such as schizophrenia, bipolar and depression, not lifelong conditions such as learning disability and autism. It is therefore wrong to apply mental health legislation to people who are disabled and not experiencing mental health issues.

The second concern is that too many people with learning disabilities and/or autism are still incarcerated in inappropriate hospital “care” – assessment and treatment units (ATUs) such as Winterbourne View and Whorlton Hall.

Today, many of these people are detained under the MHA, so it is natural to assume that if people with learning disabilities and/or autism are removed from the scope of the MHA, they might be free to leave. On the first question – whether mental health legislation does or should apply – it is important to note that the legislation itself explicitly includes “disability of the mind” in its scope (section 1(2), MHA). The intent was clearly to include longer-term disabilities as well as intermittent conditions.

In addition, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) frameworks for detention use exactly the same term and definition of “mental disorder” to define the populations who can lawfully be detained under the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) and the Liberty Protection Safeguards (LPS). The belief that the MHA should not apply to people with long-term developmental disabilities (or, similarly, people with brain injury or dementia) is cultural, not legal.

I argue in a book I am writing that this has deep historical roots in how these different populations were parsed and treated in the late 19th and 20th century, with one group deemed curable and the other incurable but perhaps trainable. Arguably, removing some populations from the scope of the MHA because it is associated with stigma is simply reinforcing that stigma for others without addressing the core problem.

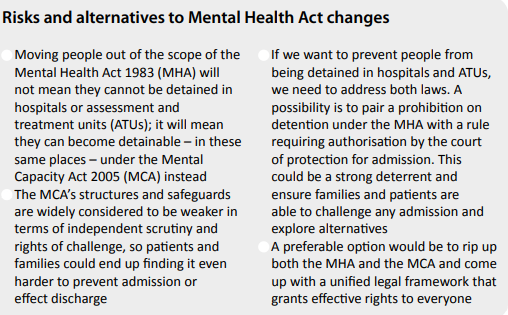

On the second assumption, I suspect many will argue that removing people with learning disabilities and autism from the scope of the MHA will mean they are less likely to be detained in hospital settings such as ATUs. While I absolutely support the intention here, I believe the opposite outcome might result. Odd as it might sound, removing people from the scope of the MHA will not actually prevent them from being detained in hospitals and ATUs, and might even make it easier to detain them where they or their families object. This is because – for complicated reasons that I will try my best to explain shortly – when you take people out of the scope of the MHA, they become “eligible” for detention under the MCA instead. The DoLS are a framework for detention within the MCA that apply in hospitals and care homes.

Inadequate new safeguards

Given the acknowledged inadequacy of these safeguards, next year the DoLS will be replaced by a new framework, the LPS. Unfortunately, the LPS are full of problems as well. So although people with learning disabilities and autism might no longer be detainable under the MHA, they could very well find themselves detained in the same places, and subject to similarly restrictive regimes and treatment (without consent) under the MCA instead. If they are detained under the MCA, they and their families will have fewer opportunities to object to or challenge their detention and treatment.

The interface between the MHA and the MCA is so horribly complicated that a senior judge described it as like putting your head in a washing machine and spin dryer. Another judge observed that people who find themselves entangled in this legal interface will have an incredibly hard time understanding and exercising their rights. To put it as simply as possible, the MCA is basically a legal overflow system for populations who have for various reasons been ousted from the MHA. This includes some people with learning disabilities (and autism, if this proposal is adopted), but it can also be true for other groups, for example, people with dementia or those with brain injuries. If a clinician deems it as being in a person’s best interests to be in hospital for whatever reason and if the person cannot consent to this, the MCA DoLS can be used to detain them.

Another example is that a person who has been detained under the MHA then discharged by a mental health tribunal because they do not meet the MHA’s criteria for detention cannot then be re-detained under the MHA. However, it seems they can then become eligible for detention under the MCA DoLS instead. So the same person could then be detained again in the same place, just under a different law. It seems perverse that you could set up a law precisely to discharge people from detention when they do not meet certain criteria, only for them to be detained again under a different law.

To summarise, the smaller you make the reach of the MHA – by raising risk thresholds, by removing people with learning disabilities and/or autism from its scope altogether – the more people will overflow into the MCA’s provisions for detention. For some people, this sounds acceptable. I have heard it argued that since it self-evidently would not be in a person’s best interests for them to be detained in hospital, the MCA will protect them against that possibility.

Best interests not the best option

The trouble is that the concept of best interests is inherently vague and subjective. I doubt there is a doctor in the country who would detain a person in hospital where they believed it was not in their ultimate best interests, albeit they might see it as the least bad option for that person from the available options.

Let’s take a hypothetical example to work this through. “Ella Brown” has autism and her care in the community is breaking down. She is considered by clinicians to pose a risk to herself as well as others and they want to bring her into hospital for assessment and treatment. At present, they could make an application for detention for assessment under section 2 of the MHA. She would not be eligible for detention under the MCA DoLS (or the LPS as presently drafted) because she is both within the scope of the MHA and she is objecting. However, if the white paper’s proposal to remove people with autism from the powers of detention of the MHA were adopted, then she would no longer be within the scope of the MHA; no application could be made under section 2 or, if it were made, it could not be granted.

So, even though Brown is objecting, she is now eligible for detention under the MCA – the DoLS at present and the LPS as of next year.

Less scrutiny

Detention under the MCA potentially means that fewer independent professionals will be scrutinising admissions and the frequency of reviews. Whereas under the MHA a tribunal will automatically be convened for Brown after six months to review her detention, the odds of her having a court review of detention under the DoLS are 1% and projected (by the government) to fall to 0.5% under the LPS.

She would no longer be eligible for free aftercare. There would be no statutory discharge planning processes of the kind proposed in the MHA white paper. There are good reasons to believe she and her family might have a harder time preventing her admission or getting her out under the MCA than the MHA.

Question the loss of protection

So, my point is this – taking people with learning disabilities and autism out of the scope of the MHA will not stop them from being detained in ATUs unless we also fix the MCA. We could argue for an absolute prohibition on hospital detention for this population or a requirement for court approval for this. We could argue that the MCA should carry safeguards equivalent to those in the MHA. This would entail a major review of the LPS, which were passed by parliament only a couple of years ago. I doubt the government would want to revisit that turbulent exercise any time soon, but it is worth asking ourselves why someone should have less protection under the MCA for detention in the same kind of setting.

- Department of Health and Social Care (2021) Reforming the Mental Health Act. https://tinyurl.com/4wtx9sdd

Lucy Series is Wellcome senior research fellow and lecturer in law, School of Law and Politics, Cardiff University. Follow her blog

The Small Places at https://thesmallplaces. Seán Kelly wordpress.com/author/lucyseries/