The concept of safeguarding has gradually taken on greater significance in social care services in recent decades. It is underpinned by legislation on data protection and mental capacity, by concepts of professionalism and by modern ethical principles of privacy and autonomy.

All social care services are expected to implement procedures to protect people’s privacy, ensure their choices are respected and prevent physical, emotional, sexual or financial abuse. This includes instructions to staff on how to behave towards those they support.

Local authority safeguarding guidance policies include provisions such as: not disclosing any personal information about someone with whom you are working to any unauthorised person (including your own family and friends); not giving personal information about yourself or your mobile or home number to people you support; not taking them to unauthorised places (including your own home); and not giving them gifts.

Staff may also be required not to show any physical affection to a person. Offering to foster or provide an adult placement for someone you support may also not be allowed.

Policies such as these are being implemented by statutory, private and voluntary social care providers throughout the country, led by legislation, by safeguarding, commissioning and inspection procedures, and by professional standards and guidance. The rules are enforced through staff induction training, inspection and regular supervision.

Staff are told this approach constitutes professionalism, and that must preclude personal relationships of friendship and life sharing. It protects people from harm, exploitation and unfairness.

However, I believe the implementation of these concepts of safeguarding can in itself constitute a major form of abuse. In my view and experience, this fails to meet a desperate need of very many people with learning disabilities.

Few friends

Has the very practice of safeguarding, designed to protect people from harm and exploitation, become a form of abuse itself? Paul Williams explores a disturbing question.

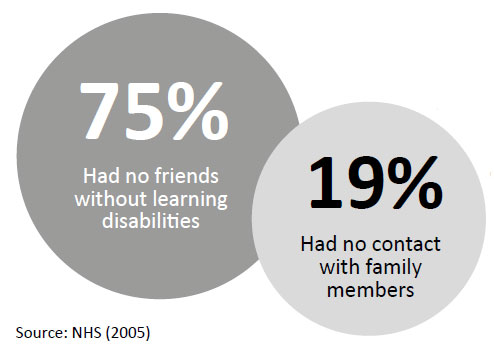

In 2005, a survey of a large sample of people with learning disabilities in England (NHS, 2005) found that 75% had no friends without learning disabilities and, of those, nearly half had no friends at all. Nearly one in five (19%) of the sample had no contact with any family members.

American writer David Pitonyak has written powerfully about people’s great need for friendship throughout life, particularly in his paper Loneliness is the Only Real Disability (Pitonyak, 2005).

Safeguarding, as currently practised, far from tackling this, actually enforces loneliness, isolation, a lack of friendship and a lack of family experience on people receiving care services.

This was brought home to me recently when I was with a person with learning disabilities and a supporter from the home where she lives. I asked her if she had a friend and she replied with the name of another member of staff, whereupon the supporter said in a stern voice: (No they aren’t. They’re not allowed to be your friend.)

The instruction to staff not to share information about themselves, not to introduce people to their family and friends, not to take people home, not to give them your phone number, simply reinforces the inequality between staff and the people they support and denies any possibility of genuine friendship. It also denies people the experience of friendship and family life.

The instruction not to talk about the person to (unauthorised) people or take them to (unauthorised) places can mean a person remains invisible and their strengths and achievements go uncelebrated in their community. Not giving gifts can mean failing to properly and reciprocally celebrate birthdays and other festivals.

If staff were allowed to offer genuine friendship to those they support, all these things would become possible and, I believe, would be welcomed by the great majority of both staff and those supported.

Supporting people with learning disabilities is long-term work. Many staff work with the same individuals for many years Đ in some cases a lifetime. This offers many opportunities for close friendship.

I know of several instances where people without a family have been taken home by one of their supporters, for example at Christmas, over many years, to stay overnight and be part of family celebrations, but the supporters have been told it is now (unprofessional) and cannot happen. There is a great sense of loss on both sides.

Tyranny versus equality safeguarding

Has the very practice of safeguarding, designed to protect people from harm and exploitation, become a form of abuse itself? Paul Williams explores a disturbing question.

Before the advent of the tyranny and risk avoidance within current notions of safeguarding, evidence showed fostering equality and genuine friendship between staff and those they support is beneficial and greatly needed.

The British Institute of Learning Disabilities in 1989 published a study of relationships between social workers and people with learning disabilities. In many cases, there was true friendship and sharing to the great benefit of everyone.

It reported: (The social worker’s task was characterised by informality. It took place within long-term relationships. Many people had their social worker’s home address and telephone number. Many social workers described themselves as friends of the people with whom they worked. Some service users shared this view and came to see their social workers as their friends too) (Atkinson, 1989).

More than 40 years ago, Values Into Action held what were called participation workshops to foster equal relationships between staff and those they supported. A whole weekend event was structured around equal sharing. Rooms, facilities and activities were shared and, if you asked a question of a person, you were expected to answer it as it applied to yourself.

A concept of (life sharing) was prevalent in organisations such as L’Arche and Camphill, deriving from their positive founding philosophies (Williams and Evans, 2013).

This concept prevails where the pressure to (professionalise) can be resisted. As L’Arche (2021a) noted: (People with learning disabilities have much to teach us and contribute to the world. During the last 50 years, we have learnt that one of the best ways to enable this is by creating a culture of shared lives between people with and without learning disabilities.)

There is mutual benefit in such relationships: (I got to know the three guys quite well over the course of the year, and it changed my life in ways that I had never expected. I was constantly amazed at how much I was growing through these friendships.

(I had thought I was coming to this programme to do a good thing and help people but actually it was me who was being cared for. I learned that I can experience meaningful, mutual friendship with people who are different from myself) (L’Arche, 2021b).

A study of a Camphill community involving life-sharing between people with learning disabilities and the extended families of their supporters came to this conclusion: (Living in extended families in a long-term social relationship with co-workers/assistants enables both groups to become familiar with each other’s pattern of communication: an essential step if a person with a learning disability is to learn of the world and express choices about what they want to do in it.

(It also helps generate a sense of community in which they feel part of a readily available, supportive and dependable social structure.) (Randell and Cumella, 2009).

A hug, a family, a different approach

Has the very practice of safeguarding, designed to protect people from harm and exploitation, become a form of abuse itself? Paul Williams explores a disturbing question.

This is what I would like to see. On arrival to support a person, staff give them a hug. When they ask a person what they’ve been doing, they tell them what they’ve been doing too.

Staff who wish to are encouraged to introduce the person to their own family and friends and to take the person home to experience family life. Birthdays, marriages, births, festivals and funerals are celebrated on both sides, with equal exchange of cards, invitations and presents.

Each person supported is helped to keep a record, for example photographs and an address book with contact details, which includes not only their own friends and family but also staff who they are close to and their family and friends.

Staff and people they support are encouraged to be each other’s friends on social media. If they leave, staff are encouraged to keep in touch and be willing to continue friendship with the person they have supported, through visits, communications and in other ways.

If staff wish to consider fostering or an adult placement, who better to do this for than someone they already know well?

Only in this way can the devastating abuse of imposed loneliness, isolation and friendlessness be tackled seriously. I believe that experience of this is common among people with learning disabilities and they are particularly vulnerable to it and concerned about it.

I also believe that being a true friend to someone and sharing your life with them is a much stronger safeguard against more direct abuse than rules and so-called (professional standards) (Williams, 2019).

Unfortunately, this issue has been exacerbated further by the Covid restrictions. Now is the time to reconsider what we are doing.

References

Has the very practice of safeguarding, designed to protect people from harm and exploitation, become a form of abuse itself? Paul Williams explores a disturbing question.

Atkinson D (1989) Someone to Turn to: the Role of Front-line Staff. BILD Publications

L’Arche (2021a) What We Do. https://www.larche.org.uk/what-wedo

L’Arche (2021b) Meaningful and Mutual Relationships. https://tinyurl.com/rxamst5j

NHS (2005) Adults with Learning Difficulties in England. Health and Social Care InformationĘCentre

Pitonyak D (2005) Loneliness is the Only Real Disability. https://tinyurl.com/9evcywwy

Randell M, Cumella S (2009) People with an intellectual disability living in an intentional community. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research; 53(8):716-726.

Williams P (2019) See people as friends to curtail abuse. Community Living; 32(4):6

Williams P and Evans M (2013) Social Work with People with Learning Difficulties. Sage