A worldwide pandemic strikes the UK. People with learning disabilities die in large numbers. This comes on top of death rates that were already high.

What can the flu pandemic of 1918 teach us about today’s pandemic and the histories of people with learning disabilities? Looking at death registers from Leavesden Hospital for the years 1918-20 raises some interesting questions. Death rates for people with learning disabilities during the Covid pandemic of 2020-21 were, according to Public Health England (PHE, 2000), six times as high as those in the general population.

Furthermore, PHE found that deaths were more widely spread across age groups, with disproportionately higher mortality rates in younger adults. People with learning disabilities aged 18-34 were 30 times more likely to die with the virus than their counterparts in the general population. To some extent, this reflects the greater prevalence of health problems such as diabetes, obesity and respiratory vulnerability in people with learning disabilities. However, the well-documented failure to protect their health was also undoubtedly a factor.

Our concerns about this prompted us to look back at a previous pandemic. The Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-19 killed between 50 and 100 million people worldwide, around 2-5% of the global population (Spinney, 2018: 1296). The records we could access allowed us to look at the impact of this epidemic on the population of a large asylum. Leavesden Hospital in Hertfordshire was one of the largest institutions, serving a diverse range of pauper patients from the northern half of London, including people with learning disabilities and those with mental health issues.

It opened to patients in 1870. It was initially planned to accommodate 1500 people in 11 blocks, each designed to hold 160 beds. The ground floor of each block was a day room and the upper floor sleeping quarters, with four toilets and two washrooms. The asylum also had its own cemetery.

Overcrowding was an issue from the start. As early as 1871, barely a year after he hospital opened, there were 1,638 patients and, in 1914, more than 2,000. Because of staff shortages during the First World War and the need to billet troops at the asylum, some patients were discharged. What Monica Diplock, who wrote the 1990 history of the hospital that is the source of this information, did not mention was that the population of the hospital declined for other reasons during the war, with extraordinarily high death rates from causes including the Spanish flu and other infectious diseases.

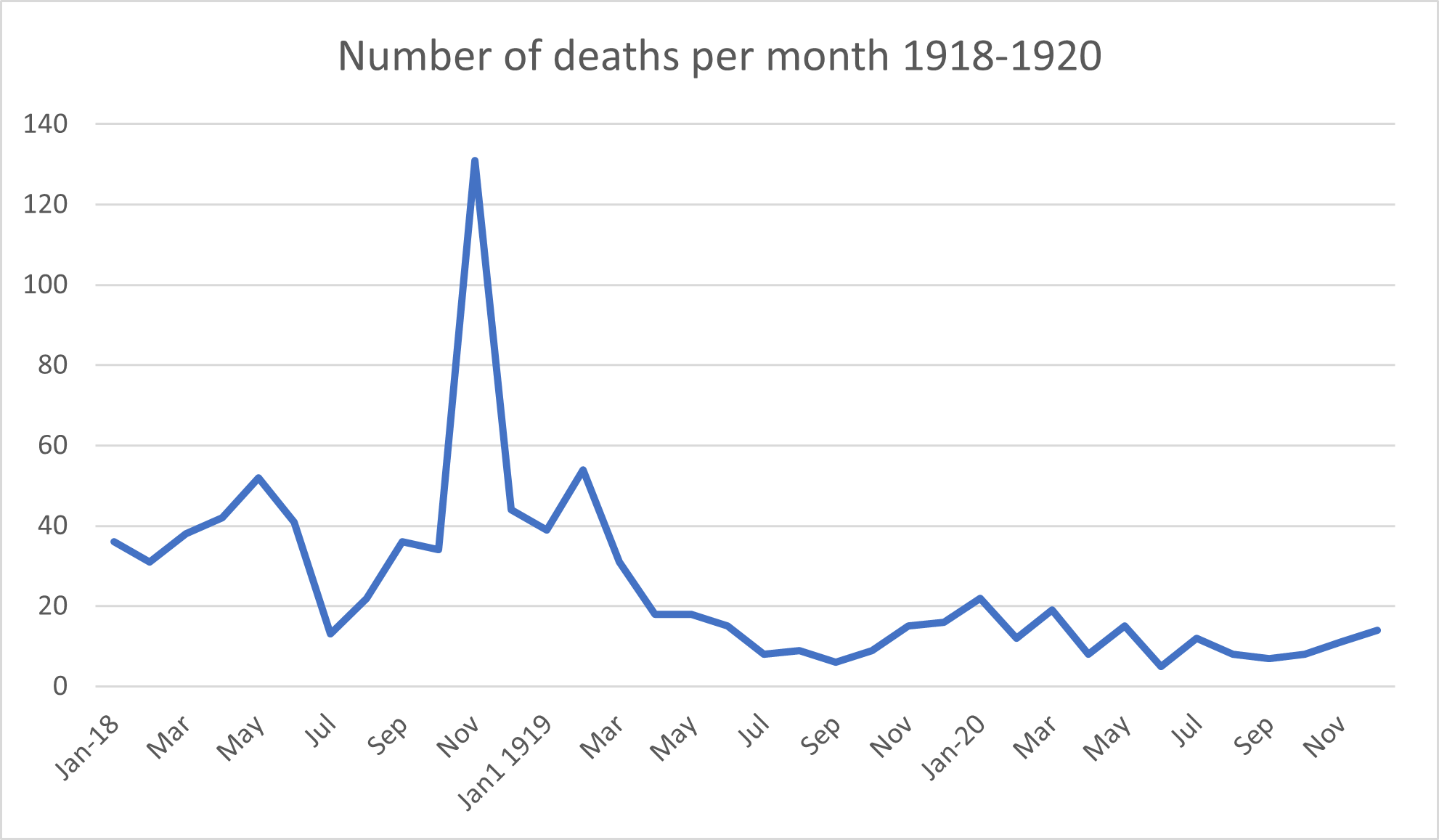

The graph below shows the number of deaths for three years: 1918, 1919 and 1920. Three features are striking. The first is that there was some seasonal variation in the number of deaths, with fewer deaths being reported for summer months generally.

The second and most obvious is the spike in deaths in November 1918. There were 131 deaths – the greatest number of deaths reported for any month in the three years. There were more than 30 deaths a week, almost eight times as many deaths than reported in November of 1919 or 1920. There were 96 burials that month. On 11 November 1918, Armistice Day, there were 10 burials – more than the total for the whole of November the following year.

The impact of the 1918 influenza epidemic is undeniable. The asylum that month was marked by death and dying. The third feature of this graph is that the number of deaths in 1918 was already elevated. In the 10 months before November 1918, there had been 345 deaths. That was almost as many deaths as in the 24 months after December 1918. Although the impact of the influenza epidemic was considerable, it does not in itself explain why deaths in 1918 were already so high. If the death rate to October 1918 had continued without the pandemic, we might have expected there to be about 434 deaths in that year, a number still several times higher than seen in 1919 and 1920.

It was not until the spring of 1919, some four months after the last recorded influenza death, that the number of deaths seems to fall appreciably below any month of 1918. However we look at it, the influenza epidemic killed many residents yet it explains only partly why the number of deaths in 1918 was so high.

Casualties of war

The records we have access to give a complete account of death and dying in Leavesden only from August 1917. Gwendolen M Ayers’ book England’s First State Hospital and the Metropolitan Asylums Board 1867-1930, published in 1971, shows that for every year of World War One, the number and proportion of deaths in asylums run by the board was increasing.

In 1914, 11.2% of people living in asylums died in them. In 1918, this figures had risen to 27.0% – more than one in four residents. The average proportion of deaths in the four years before 1914 was 9.4% of the asylum population and, in the four years after 1918, it was 13.1%. In most years, tuberculosis (TB) was the leading cause of death, accounting for more than 40% of deaths in 1919 and 1920 but only 30% of deaths in 1918.

shows the extent of the site

The 1918 influenza epidemic took root within a setting where the health status of many was already compromised. In those years, there may have been food shortages. There were certainly fewer staff since some had been conscripted into the armed services. Some wards were closed and this probably led to more than the usual overcrowding in others. These were ideal conditions not just for the influenza virus to spread but also for the ravages of TB to take most effect. The daily burial toll on Armistice Day 1918 is perhaps a symbolic reminder that the higher profile of death in the asylum in 1918 was as related to the effects of the First World War as it was to a virus – these were victims of war.

Finally, the decline seen in deaths from 1918 suggests that the end of the war and the epidemic brought about a return to lower levels of deaths in the asylum. However, it was a return to a death rate that was still high. Few may have asked at that time whether around one in 10 people in the asylum dying every year was acceptable.

As we say above, the risk of death for people with learning disabilities is elevated in the UK during the current pandemic. It was high even before this. We ask ourselves: do we find it acceptable for mortality to return to pre-Covid levels in the 21st century?

References

Ayers G (1971) England’s First State Hospitals and the Metropolitan Asylums Board 1867-1930. University of California Press Diplock M (1990) The History of Leavesden

Hospital. http://www.leavesdenhospital.org/document-archives/

Public Health England (2020) Deaths of People Identified as Having Learning Disabilities with COVID 19 in the Spring of 2020. London: PHE.

https://tinyurl.com/y2lj93p9

Spinney L (2018) Pale Rider: the Spanish Flu of 2018 and how it Changed the World. Penguin Random House

Weaver M (2020) Covid deaths for people with learning disability in England six times average. The Guardian. 12 November. https://tinyurl.com/y39ecuxg